Our Philosophy

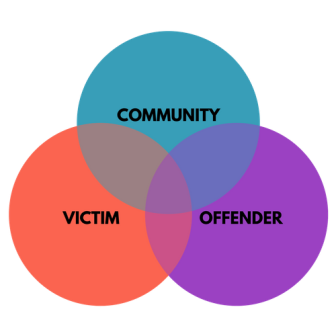

Probation services within ACJCS are based on a restorative justice framework. Restorative justice is concerned about the relationships between offender, victim, and community; it gives priority to repairing damage or harm done to victims and their communities. Restorative justice differs from retributive justice in its view of crime as more than simply breaking the law. Rather, the most important function of justice is to ensure that harm to victims is repaired.

The balanced approach to juvenile justice works within the restorative justice framework and includes the following principles:

Community Protection

The public has a right to safety and security within the community.

Competency Development

Offenders should leave the juvenile justice system more capable of productive participation in society than when they entered.

Accountability

When a crime occurs, a debt is incurred. Juvenile offenders must be held accountable for their actions, and restore the victim’s losses.

What sanctions or consequences for the offender should mean to various parts of the juvenile justice system:

Community

Requiring offenders to repay victims for their crimes receives the highest priority in the juvenile justice system. The community is a key player in holding offenders accountable.

Offender

Your actions have consequences; you have wronged someone through your offense. You are responsible for your crime and capable of restoring the harm or repaying the damages.

Victim

The juvenile justice system believes victims are important and will do its best to ensure that, to the degree possible, the offender repays the debt incurred from the crime.

Our History

HISTORY LESSONS – JAIL, JUVENILES, AND JUSTICE: Ada County Juvenile Court Services’ Journey GENESIS (1900s – 1974)

HISTORY LESSONS – JAIL, JUVENILES, AND JUSTICE: Ada County Juvenile Court Services’ Journey GENESIS (1900s – 1974)

Written by Barbara Leonard, Former Ada County Juvenile Court Manager

Ada County began hearings for juveniles at the turn of the century. Earliest recorded documents of Ada County indicate hearings were held in Probate Court and presided over by a Probate Judge. Investigations were done in the home to determine whether the case was child neglect or juvenile delinquency.

Court personnel included a court investigator/probation officer and a female caseworker who provided services to juveniles. While the crimes committed by these turn-of-the-century youths appeared to have been mostly theft related, other offenses, such as wandering the streets, incorrigibility, running away from home, possessing tobacco or alcohol, associating with immoral persons, and loitering were also noted. Boys committed most of the offenses, as is still true today.

A no-nonsense approach to juvenile delinquency seemed to be the theme of court philosophy in the early days. A child who committed several offenses, however minor, would be committed to the Idaho Industrial Training School in St. Anthony, Idaho. This institution was constructed in 1900 and was operated by the State Department of Education. It was built specifically for dealing with children who were out of control or abused. In due time, the training school evolved into a typical “reform school” and was used for neglected children as well as delinquent children. Often residents remained at the school until age 21. Other typical sentences included fines of $10.00 payable over a period of ten months, probation for up to one year, and a requirement to stay off the streets after 7:30 p.m. Eventually, juveniles began to be placed in the city jail, located at Sixth and Jefferson in Boise. A hallway in this facility separated juveniles from adults.

Several court documents provide some insight into early juvenile justice. The following examples are indicative of court decrees from this time:

May 1, 1922, a 13-year old boy appeared before Probate Judge D.J. Miller having been charged with delinquency for “helping to take a bicycle from Cody Park.” The boy was given parole and told that his next appearance would result in commitment to the Idaho Industrial Training School in St. Anthony, Idaho.

May 2, 1924, a 14-year old boy was truant from school, ran away from home, and stole a horse “not his property.” Luckily, the boy lived in the 1920’s instead of the 1800’s when horse thieves were not treated too kindly.

August 12, 1924, a boy appeared before Judge F.E. Chalfant, Sr. for stealing a watermelon from a stand at Eleventh and Grove in Boise. The boy was committed to the Idaho Training School for this crime.

October 15, 1925, a female caseworker was ordered to deliver a 14-year old girl to the Idaho Industrial Training School “at St. Anthony, in Fremont County, State of Idaho.” Automobiles at this time did not provide much comfort for passengers, especially on trips covering over 300 miles of dirt roads.

Except to accommodate population increases, the courts continued with little change until the Idaho legislature passed the Youth Rehabilitation Act in 1963. This Act allowed counties to establish juvenile probation departments separate from the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. Soon after that, Administrative Judge E. Smith moved juvenile hearings from Probate Court to District Court. By this time, four or five Magistrates worked in the courthouse, and these Magistrates took turns hearing juvenile cases. Caseworkers then numbering three males and one female did not know until the last minute which Judge would be “handling juveniles” that day.

THE WAY WE WERE (1974 – 1994)

Written by Barb Dauner, Former Ada County Juvenile Court Probation Officer

Written by Barb Dauner, Former Ada County Juvenile Court Probation Officer

Gladys Records began her employment at Ada County in 1962. Although she began as a detention officer, shortly thereafter she was reassigned to a probation officer position. She made the transition from the Ada County Courthouse on Jefferson Street to the current Ada County Juvenile Court on Denton Street and remained with the agency until her retirement in the mid-1980s. Her reminiscences provide the bulk of the following information:

In 1974, the philosophy of juvenile justice was that juvenile delinquents came from bad families. The thinking at that time was that if the mother worked outside the home, the juvenile would be delinquent.

Strategies of rehabilitation were limited and included keeping juveniles busy or removing them from their homes. Community placements were rare. Relatives were often called upon to fill the need for out-of-home placements. Booth Memorial Home provided a place for pregnant teens to live. Confinement in detention was used for juveniles who were perceived to be “bad”, and no other placements were available. One problem that complicated things and frustrated the Magistrates was that the detention beds were nearly always full. This was because Ada County contracted with other counties to house their offenders in its facility. Another placement available at that time was the Children’s Home on Warm Springs Avenue.

Sometimes, if probation officers didn’t believe a juvenile should be placed in detention, they would take the juvenile into their homes until other arrangements could be made for placement. Ms. Records remembered one girl who she took to her own home for two weeks because no other placement was available. Since it was Christmas time, Ms. Records’ family gave the girl a Christmas stocking and gifts.

Probation officers also often felt that it was part of their job to give money to help juveniles who were on probation. On one occasion, Ms. Records paid $15 to get a juvenile’s car “out of hock” so the juvenile could return home to Minnesota.

During this time, few services were offered in the community to assist clients; therefore, probation officers would help juveniles find jobs so they could pay restitution to their victims. Probation officers also made recommendations that juveniles be ordered to attend Bishop Kelly High School, a private Catholic school, for a more structured educational setting. If the probation officer believed a client was suicidal, all the officer could do was hope the client did not follow through, as there were few services and no local, in-patient psychiatric facility.

In 1974, often one felony crime was sufficient for commitment to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and placement at the Youth Services Center, previously known as the Idaho Industrial Training School in St. Anthony, Idaho. Even habitual status offenders were sent to this facility. The community favored commitment to the Department of Health and Welfare because juveniles on probation were perceived as “bad.”

Also in 1974, there were no specific juvenile law enforcement officers. Therefore, when problems arose with a juvenile during the night, the probation officer would often be called. Probation officers were considered on call 24-hours a day, which is still true today.

Just as today, in the early 1970s, probation officers dealt with some serious juvenile offenders. Ms. Records recalled working with two juveniles who attempted to smother a 60-year old man so they could steal his social security check. Other juveniles were on probation for kidnapping and robbery. A particular juvenile that Ms. Records remembered was originally assessed as coming from a “nice” family and thought to be “ok”, but as an adult, he was arrested as a serial rapist. Ms. Records also recounted an incident where a juvenile in detention hit her over the head with a rod (actually a crank-handle from the crank-up beds). Despite a cut to her head that required stitches, she was able to get to the control room and press a buzzer to call the sheriff. The prosecutor wanted to try the juvenile as an adult but decided, instead, to keep the case in juvenile court as the detention facility had only been in operation for two months.

Ms. Records had many sad and happy recollections. She felt that it was always sad when a client with whom a probation officer had worked diligently returned to juvenile court as the parent or grandparent of a youth who was in trouble with the law. It was frustrating, also, to learn that the probation officer’s influence and the court experience had made little impact on family generations. Conversely, happy moments occurred when ex-clients, now adults, returned to let her know how they were doing and to thank her for her help during that period in their lives when they were struggling to stay on the right side of the law.

TEN YEARS AFTER (1994 – 2004)

Written by Jim Meliza, Former Ada County Juvenile Court Probation Officer / Supervisor

Written by Jim Meliza, Former Ada County Juvenile Court Probation Officer / Supervisor

In 1994, agency Director Art Dodson, MSW, wrote: “1994 promises to open all kinds of creative possibilities for change. The Idaho Legislature has authorized a special legislative committee to completely study Idaho’s juvenile justice system and report to the Legislature in January 1995 when the new governor takes office. There is much interest in forming a unified system to pull together Idaho’s fragmented non-system.”

Mr. Dodson predicted the Legislature’s decision to move juvenile justice from the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and to form a new agency, later to be called the Idaho Department of Juvenile Corrections. He also forecasts the Legislature would find alternative funding for county probation departments, change the confidentiality rule for juvenile cases, identify victims’ rights in juvenile court proceedings, and reform the use of secure detention facilities.

In 1995, the Idaho Legislature passed the Juvenile Corrections Act. Upon its signature by Governor Dirk Kempthorne, the face of juvenile justice in Ada County and throughout Idaho changed significantly. Probation staff in Ada County alone, which had numbered 16 officers, grew to 33. This allowed for an expansion of the diversion program, field probation, and intensified supervision probation. New alternative funding assisted in the expansion of programming for all clients. Kay Carter, Ph.D., headed a division which developed programs to provide mentors for youth, mediation opportunities for victims, employment opportunities for clients, and educational process groups for clients and their families. She also assisted in the creation of the Work and Learn Consortium, an alternative education program for youth who were ineligible for enrollment in traditional schools in their home districts.

Between 1999 and 2004, Ada County Juvenile Court Services expanded its outreach into the community by forging and renewing alliances with local school districts, law enforcement agencies, and community-based agencies, such as the YMCA and the Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs. Probation officers were assigned to specific schools to act as liaisons between the agency and the schools. Probation officers also began working more in the field and less in their offices.

History still in the making….